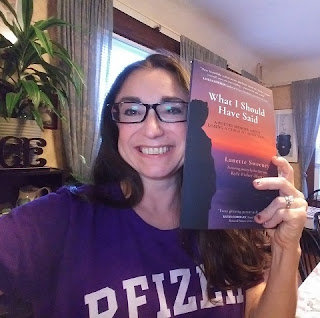

BIO

Lanette

Sweeney's debut collection, What I Should Have Said: A Poetry Memoir About

Losing A Child to Addiction, was

published by Finishing Line Press in August, 2021. Sweeney is grateful the book is allowing her to share

two messages: first, medication-assisted treatment saves addicts’ lives and should not

be stigmatized, and second, a life rich with joy and meaning is (eventually) possible

after even the most devastating loss.

Sweeney’s

essays, articles, short stories and poems have appeared in daily newspapers, print

and online literary magazines (including Rattle,

Amethyst Review, Gyroscope, Tigershark, Blue Collar Review, Please

See Me, Foliate Oak Review, and Misfit Magazine), as well as in anthologies (including Prima Materia, Silkworm, and the Center for New

Americans annual review), and in textbooks, including several editions of the popular college-level women’s

studies textbook Women: Images and

Reality published by McGraw Hill. Her essays, blog posts and book reviews can be seen on her website, https://www.lanettesweeney.com

After working as a fundraiser, teacher, waitress, reporter, editor, and non-profit executive, Sweeney is grateful to now be a full-time writer thanks to her wife's support. She and her wife and their small-pet army (which consists of a dog, cat, kitten, and puppy) live in South Hadley, MA, in the house where their wedding was held 16 days before Sweeney's son overdosed. Sweeney has one surviving child, a daughter, 29, who is a teacher.

ABOUT THE BOOK

What I Should Have Said: A Poetry Memoir about Losing a Child to Addiction recounts a mother's grief, guilt, sorrow, and search for meaning after her 26-year-old son's death by overdose. The book is divided into the stages of grief, with sections on denial and depression, anger, bargaining and, eventually, acceptance. Sweeney's son's poems appear throughout the collection, often in seeming conversation with his grieving mother's words. The author hopes the book demonstrates that even the most devastating grief can result in post-traumatic growth and that medication-assisted treatment saves lives and should not be stigmatized.

Both poets and laypeople have given the book excellent reviews, calling the poems "beautifully crafted" and "poignant." Multiple reviewers noted that once they started the book, they couldn't put it down. The president of Bereaved Parents of the USA said "every grieving parent will relate" to the book and noted it helped her process her own grief about her son's death. The book can be ordered from local bookstores, Amazon, Bookshop.org or Goodreads.com.

PRESS RELEASE

FOR

IMMEDIATE RELEASE:

OCTOBER 10, 2021

CONTACT: Lanette Sweeney, (845) 527-6616, lanettesweeney@gmail.com

VIRTUAL READING SCHEDULED FOR NOV. 4TH:

AS OVERDOSES

SKYROCKET, NEW BOOK OFFERS

COMFORT TO GRIEVERS, HOPE TO ADDICTS

South

Hadley, MA, USA – Following the nation’s worst year ever for overdose deaths, a

timely new poetry collection, What I

Should Have Said: A Poetry Memoir about Losing a Child to Addiction, aims

to bring comfort and encouragement to addicts and their families. The author, along with another mother and author who lost her child to addiction, will be reading from their books in a virtual event hosted by the Odyssey Bookshop on Thursday, Nov. 4th at 7 p.m. You can register for that reading here.

Lanette

Sweeney’s debut collection describes the pain of watching her son suffer with

addiction as well as her enormous grief and guilt following his overdose death

in 2016. Fortunately, the book also offers hope to families suffering a similar

loss or struggling with a child still in active addiction, as Sweeney lyrically

recounts her journey toward post-traumatic growth and grief recovery, as well

as what she’s learned can save addicts’ lives.

“I have two messages I’m eager to share with

this book,” says Sweeney: “first, that most addicts need medicine to keep them

alive, so taking medicines like Methadone and Suboxone should not be shameful;

and second, that it is possible to restore peace and joy to your life after even

the most devastating loss.”

What I Should Have

Said

was released last month by Kentucky-based publisher Finishing Line Press. The

book is organized into sections on the stages of grief and includes 20 poems by

Sweeney’s late son, Kyle Fisher-Hertz, showing his move from the innocence of

childhood to the eventual despair of his addiction.

“My

son wanted to get better,” Sweeney recalls. “He attended every recovery program

he could get into. But then he turned 26, my insurance didn’t cover him

anymore, and the Medicaid insurance he got as a replacement didn’t cover the

monthly shot that had helped him stay clean.”

Sweeney’s

son spent the week before his death pleading for help from the only recovery clinic in the state where he was then living, Nevada, but he was

refused the drug he requested, Vivitrol, which is a monthly shot that blocks

opioid receptors and reduces cravings. (A desperate addict’s quest to stay

clean long enough to get the shot is depicted in the new film Four Good Days, starring Glenn Close and

Mila Kunis.) At the time of Fisher-Hertz’s death nearly five years ago,

Medicaid in 29 states didn’t cover that medicine, whose generic name is

Naltrexone–and Fisher-Hertz, like many addicts, was reluctant to take Methadone

or Suboxone, the maintenance drugs he was offered. Instead, he died of an

overdose of street drugs three days later–less than three months after turning

26 and losing his mother’s private insurance.

“I

foolishly didn’t think he should take maintenance drugs, either.” Sweeney says.

“When he called me to say he was thinking about taking one because he didn’t

know what else to do, I stayed silent, and he knew I didn’t approve. When he

died three days later, I knew I had discouraged him from taking the one thing

that might have saved his life, and my guilt was devastating. I wish I’d known

when he was alive that he had a terminal disease that needed medicine to treat

it.”

Poet

Lesléa Newman, author or editor of more than 70 books, calls Sweeney’s poems “poignant” and “beautifully crafted.” She

says she “read this collection straight through with [her] heart in [her]

throat” and adds: “Reader, prepare yourself: once you start reading What I Should Have Said, you won’t want

to stop.”

Praise

for the book comes from outside the poetry world, as well. The president of the

board of Bereaved Parents of the USA, Kathy

Corrigan, lost two sons and says “Every grieving parent will relate” to the

feelings expressed by Sweeney in this “deeply moving” and “honest” work.

Reading the collection, Corrigan says, helped her process the grief she felt

over losing her second son, who died two years ago from alcohol addiction.

Corrigan said she appreciates that the collection “sheds light on the darkness

and stigma attached to the disease of addiction and [reminds] us that our

children were/are so much more than their addiction[s].”

The

U.S. had been starting to turn the tide on overdose deaths in 2019, but then the

pandemic arrived, causing isolation, 12-step meeting cancellations, the

slashing of addiction treatment programs, new economic stresses, and fresh

grief. As a result, the monthly overdose

death rate shot up 50 percent in the early months of the pandemic, to more than

9,000 deaths a month; prior to 2020, U.S. monthly overdose deaths had never risen

above 6,300.

The

annual overdose death rate also rose to heartbreaking new heights last year;

the CDC anticipates that when the final numbers are in, more than 90,000

individuals will have died of an overdose in 2020 (80 percent from opioid

overdose) – up from about 70,000 the previous year.

Sweeney’s book can be ordered directly from the author or from local bookstores or Bookshop.org or Amazon or from the publisher at https://www.finishinglinepress.com/product/what-i-should-have-said. Sweeney is available to do readings from her book and take part

in panels or Q&As via Zoom or other event platforms at schools, bookstores,

libraries, recovery programs, harm-reduction centers, and any other venue

interested in hearing her story and words of encouragement. For more

information or a review copy of the book, contact Lanette Sweeney directly at lanettesweeney@gmail.com or on her website lanettesweeney.com.

* * *

Sources

for Statistics:

https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2021/spike-drug-overdose-deaths-during-covid-19-pandemic-and-policy-options-move-forward citing CDC statistics

https://www.overdoseday.com/facts-stats/ United Nations

Office on Drugs and Crime.

BOOK COVER

PRESS LINKS

https://www.poughkeepsiejournal.com/story/life/2021/09/10/what-should-have-said-memoir-son-who-died-addiction/5576567001/

Straw Dog Writer's Guild featured Lanette Sweeney in an

author interview on Sept. 13, 2021.

Kenyon Review columnist Ruben Queseda did

an interview with Sweeney for his Poetry Today column in late April, 2021. (Sweeney's is the second interview on this page.)

What I Should Have Said: A Poetry Memoir about Losing A Child to Addiction was featured in mid-September as a top choice on the weekly book-recommendation email sent by our local library,

Wowbrary.

APPEARANCES

UPCOMING:

On Thursday, Nov. 4, 2021, join the Odyssey Bookshop in South Hadley, MA, at 7 p.m. as they host a virtual reading with poet memoirists Lanette Sweeney and Miriam Greenspan, both mothers of children lost to addiction. Lanette will read from What I Should Have Said: A Poetry Memoir About Losing a Child to Addiction. Miriam will read from The Heroin Addict’s Mother: A Memoir in Poetry.

Both mothers' books were published in 2021. Greenspan, M.Ed., LMHC, is an internationally renowned psychotherapist and author. Her pioneering book, A New Approach to Women and Therapy, helped define the field of feminist therapy, and her Boston Globe best-seller Healing Through the Dark Emotions: The Wisdom of Grief, Fear and Despair, won the 2004 gold Nautilus book award in the self-help/psychology category.

PAST:

On Sept. 18, 2021, Lanette Sweeney was a featured speaker at the Highland Public Library, the library where she took her children as she was raising them in the Hudson Valley in NY. She did a one-hour long reading and q&a session from her book.

On Sept. 13, 2021, Lanette Sweeney read a poem by her son, "Liquor Bottle Might As Well Be a Pistol," at a CAPE (Center for Addiction Prevention and Education) event at Shadows on the Hudson Valley; she gave that evening's proceeds from the sale of her book to CAPE, which arranged to have the Mid-Hudson bridge, seen behind the speakers, lit up in purple in honor of the event.

Also on Sept. 18, Sweeney read one of her poems at a Keep it Moving walk/run event. Keep It Moving Zane is a non-profit that provides Narcan training and healthy activities for children in honor of the founder Lauren Mandel's late son, who died of an overdose one week after starting his first social work job at age 22. Sweeney read "To My Son on His 18th Birthday," and gave a portion of that day's proceeds to Keep It Moving.

On Sept. 7th, Sweeney was the featured reader at the monthly Writer's Night Out/In sponsored by Straw Dog Writers' Guild.